If we are being honest, hosting DataLad datasets is not the most straightforward thing in the world. Sure, through the power of git-annex, and with the help of a range of DataLad extension packages they can be put pretty much anywhere. But the fact that it is possible does not imply simplicity.

There used to be a time when GitLab supported git-annex repositories directly. But with the arrival of Git LFS it got removed. And Git LFS is really no match for git-annex data logistics, so none of the big hosting solutions offer any help here.

From the beginning, DataLad offered a simple web UI for read-only browsing of datasets. But for the longest time, GIN was, to my knowledge, the only complete hosting solution with built-in git-annex support. There is a public instance, and it allows for private repositories. But not all data can be uploaded to this science-focused service. Although GIN is open-source (a fork of Gogs) and can be self-hosted, setting it up isn’t so straightforward either, and its development has not kept up with Gogs over the years.

Not so long ago, the forking of Forgejo from Gitea brought some change to the Git hosting landscape. Forgejo is now the solution underlying codeberg.org, a Git forge hosting >100k projects with ~90k users. It is backed by a non-profit, specifically focused on keeping the software free and open-source (unlike the open-core models of alternatives like GitLab). Moreover, Forgejo is specifically aiming to be a self-hosted alternative to GitHub that offers “a familiar environment to GitHub users, allowing a smooth transition to a platform you own”.

And now there is forgejo-aneksajo, a Forgejo variant that adds support for git-annex 🤯.

Matthias Riße is presently pushing this effort. It is based on earlier work by Nick Guenther and others (see https://github.com/neuropoly/gitea). I have first heard about it at distribits 2024 in his unconference contribution. It was originally built on Gitea and continues to be used for the Atmospheric Research Data Information System (ATRIS) at Forschungszentrum Jülich.

If you are wondering, like I was: “aneksaĵo” is Esperanto for “annex”, just like “forĝejo” is Esperanto for “forge”. Forgejo-aneksajo is an annex forge.

Self-hosting on a Raspberry Pi

Also check out this follow-up post for a podman/system-based deployment, entirely in user-space.

My aims were similar to that of my setup for self-hosted music streaming from a DataLad dataset. I want everything to run on my series 5 Raspberry Pi. Ideally, it would run as an additional service, and due to its low requirements not require its own machine. I was hoping for the setup complexity to be minimal. And even more, I was hoping for not having to interact with the UI a lot, and certainly not having to learn another API.

With Forgejo-aneksajo being Forgejo with git-annex support, the deployment should be similar to vanilla Forgejo. That one is advertised to be “Easy to install and maintain. Hosting your own software forge does not require expert skills.” Nice.

I decide to go for a Docker-based installation. In

contrast to Forgejo, no Docker images are readily available for

Forgejo-aneksajo, and they need to be built. Knowing that one can build a

software helps to gain confidence that things can actually be fixed when there

is a need, so self-building is fine. However, the docker v20 that I installed from

the standard package sources of Debian 12.6 (stable) on my Raspberry Pi with

$ sudo apt install docker.io

could not do it out-of-the-box. It needs the buildx plugin. Fortunately, it can be added to the Debian Docker installation, and I did not need to replace it entirely. Binaries are available from the project’s releases on GitHub. I did

$ mkdir -p ~/.docker/cli-plugins

$ wget -O ~/.docker/cli-plugins/docker-buildx \

https://github.com/docker/buildx/releases/download/v0.16.1/buildx-v0.16.1.linux-arm64

$ chmod +x ~/.docker/cli-plugins/docker-buildx

and had docker buildx working. In order to be able to interact with Docker

using my normal user account, I added myself to the docker group. This

should not be done carelessly. Members of this group have elevated permissions

on the system.

$ sudo adduser $(id -u -n) docker

From here, building the Docker image was straightforward. Clone the repository

$ git clone git@codeberg.org:matrss/forgejo-aneksajo.git

and let Docker build the image based on the included Dockerfile.

$ cd forgejo-aneksajo

# check out the specific version we want to build here

$ git checkout v7.0.5-git-annex1

$ docker buildx build --output type=docker \

--tag forgejo-aneksajo:7.0.5-git-annex1 --tag forgejo-aneksajo:7-git-annex .

The build took 18 min on the Raspberry Pi. It was twice as fast on my laptop. The outcome was a 300 MB image.

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

forgejo-aneksajo 7-git-annex c95a6115bc49 About a minute ago 293MB

...

Next, I set up a system user and a location on the host system for Forgejo to

deposit files and directories outside the container. I went for a forgejo

system user and a forgejo group. For reasons specific to my Raspberry Pi

setup, I put the forgejo system user home directory at /home/forgejo and

used that as its main data directory.

$ sudo addgroup --system forgejo

Adding group `forgejo' (GID 115) ...

Done.

$ sudo adduser --system --ingroup forgejo --home /home/forgejo forgejo

Adding system user `forgejo' (UID 109) ...

Adding new user `forgejo' (UID 109) with group `forgejo' ...

Creating home directory `/home/forgejo' ...

Now, I could start the container. There are many ways to do this, and the

Forgejo docs

recommend using docker-compose. I did not

want another piece and used docker run directly.

$ docker run \

--detach \

--rm \

--name forgejo \

--hostname forgejo \

--env "USER_UID=109" \

--env "USER_GID=115" \

-v /home/forgejo:/data \

-v /etc/timezone:/etc/timezone:ro \

-v /etc/localtime:/etc/localtime:ro \

-p '3000:3000' \

-p '2222:22' \

forgejo-aneksajo:7-git-annex

This long-ish command more or less reflects the docker-compose configuration.

Important is to pass the UID/GID of the forgejo user to the container,

and to expose (-p) the ports of the web UI and the Forgejo SSH server. The

latter I wanted to listen on port 2222 on the host, because 22 was already

used by another server. We will get back to that in a second.

I set up my home network to make the Forgejo web UI available at

http://git.pididdy.local using a DNS configuration in

Pi-hole, and a reverse proxy setting in

caddy, both also running on the Raspberry Pi. This

is not necessary at all, but I like it that way.

With this done, I could go to http://git.pididdy.local and be greeted by

Forgejo with the initial setup. I left everything at default, except for

removing the “Git LFS root path” (I do not want Git LFS), and I changed the

“SSH server port” to 2222. The latter reflects where my setup exposes

SSH access to Forgejo and it makes Forgejo show the correct SSH URLs in

its UI.

At this point, one could configure more things, like email, or an admin account. I did not do any of that. Email is not required. And without a dedicated admin account, the first registered user automatically becomes admin too. Importantly, by default Forgejo uses SQLite. You can configure a proper SQL server, but for small-ish deployments this can be avoided and helps substantially with keeping the maintenance burden low.

There was one last thing to do: Enable git-annex support. For that, I added a config setting to the main configuration file.

$ sudo -u forgejo sh -c 'printf "\n[annex]\nENABLED = true\n" \

>> /home/forgejo/gitea/conf/app.ini'

After a restart of the container

$ docker restart forgejo

everything was working, I could register a user, sign-in, create and interact with projects.

Great!

The Forgejo UI felt snappy, despite running on a Raspberry Pi. It has all the goodness that I am used to from GitHub and friends. Pushing, and then browsing a DataLad dataset with hundreds of commits and several 10k files was fast and did not make Forgejo sweat (nor the Raspberry Pi).

Forgejo, unlike GitHub, does not limit the number of items in a directory listing. So when I pushed a test repository with 45k submodules (yes, 45k), it struggled loading the page completely. That being said, the UI remained responsive, albeit with a high latency. At the same time, the system load remained at less than 2%. The issue with (root) directories with many items is already known.

Most importantly, DataLad interoperability was instant – no fiddling required. Transfer of annexed files to and from Forgejo worked fast and reliably. Forgejo shows the size of a repository, including the annexed file content. I can click on annexed music or video files and play them directly from the Forgejo UI.

Amazing!

At this point I was quite happy already. But Forgejo also supports push-to-create. So I added

[repository]

...

ENABLE_PUSH_CREATE_USER = true

ENABLE_PUSH_CREATE_ORG = true

to the app.ini configuration file, and restarted the Docker container.

Now I can go to any repository or DataLad dataset, add a remote and push immediately – no required interaction with the web UI whatsoever. This means that the commands

$ git remote add pididdy ssh://git@git.pididdy.local:2222/mih/mydataset.git

$ datalad push --to pididdy

are 100% sufficient for depositing a dataset on my Forgejo-aneksajo instance, including all annexed file contents.

This is absolutely amazing, because it requires no learning of any API, no implementation of a dedicated create-me-a-project command when one needs to work with a thousand datasets, no separate API token, etc. Just push-to-create. Forgejo even extends this approach to the creation of pull-requests.

This is amazingly simple and useful. It allows anyone who is not interested in web UIs to stick to whatever Git-powered workflow they have, and still collaborate with people who prefer or need a graphical interface. I love it!

Behind the curtain

When running a large or institutional deployment, a certain complexity of a service setup is to be expected, for example from integrations with identity providers for single-sign-on, or storage systems.

For a small home or lab deployment expectations are different. Maintenance requirements should be low. There should be an “exit strategy” for when a solution can no longer be employed, and a migration is needed. What is necessary to do an effective backup? What would disaster recovery look like?

The Forgejo documentation provides instructions on doing backups, and a look at the directory structure in its working directory shows a clean separation of repository data and Forgejo database and assets.

$ tree /home/forgejo -d

/home/forgejo

├── git

│ └── repositories

│ └── <orgname/username>

│ └── <reponame>.git

│ ├── annex

│ │ ├── <hashdir_lower annex>

│ │ └── ...

│ ├── <bare git repo>

│ └── ...

├── gitea

│ └── <Forgejo DB and assets>

└── ssh

All repository data, including their annexes, are in the git/repositories/

directory. They are organized by user account or organization. Each repository

is a standard bare Git repository. If it has an annex, it is using the

hashdir-lower object tree layout that is the standard for bare repositories.

This means that these repositories in this exact organization could also be

used directly, for example for cloning and annex-get’ing data, even when the

whole Forgejo database is no longer accessible.

It was good to see that user sign-ups can easily be disabled entirely in the configuration file.

[service]

DISABLE_REGISTRATION = true

For small deployments it is often much more feasible and also leaner to have an admin create the few necessary accounts manually (via the web UI), rather than setting up email, or OpenID, or having to deal with spam and abuse coming for an open sign-up feature.

Takeaways

I think this is the best solution for self-hosting DataLad datasets that is

around at this point. It is easy to deploy. It runs on a Raspberry Pi just

fine, so it will run on pretty much anything that any lab will have in use. The

user interface is pleasant to work with and feels intuitive. The necessary

buy-in (how much one needs to adjust and adapt when adopting Forgejo-aneksajo)

is low – if anything it is even lower than with GitHub or GitLab, considering

the push-to-create feature. The risk of adoption also feels low. Forgejo

itself is very actively developed and the enthusiasm on social media for it

(#forgejo) seems substantial. Of course, the git-annex add-on by

Forgejo-aneksajo is an independently developed smaller project that can

hopefully be integrated with Forgejo directly, or at least attract a good number of

contributors to ensure its continued development.

Is the git-annex integration offered by Forgejo-aneksajo perfect already? No. The issue tracker documents problems and opportunities. But does it work? Absolutely!

After this first test, I will definitely keep using it at home, and will look into further adoption at work, and making sure that DataLad continues to work well with Forgejo-aneksajo!

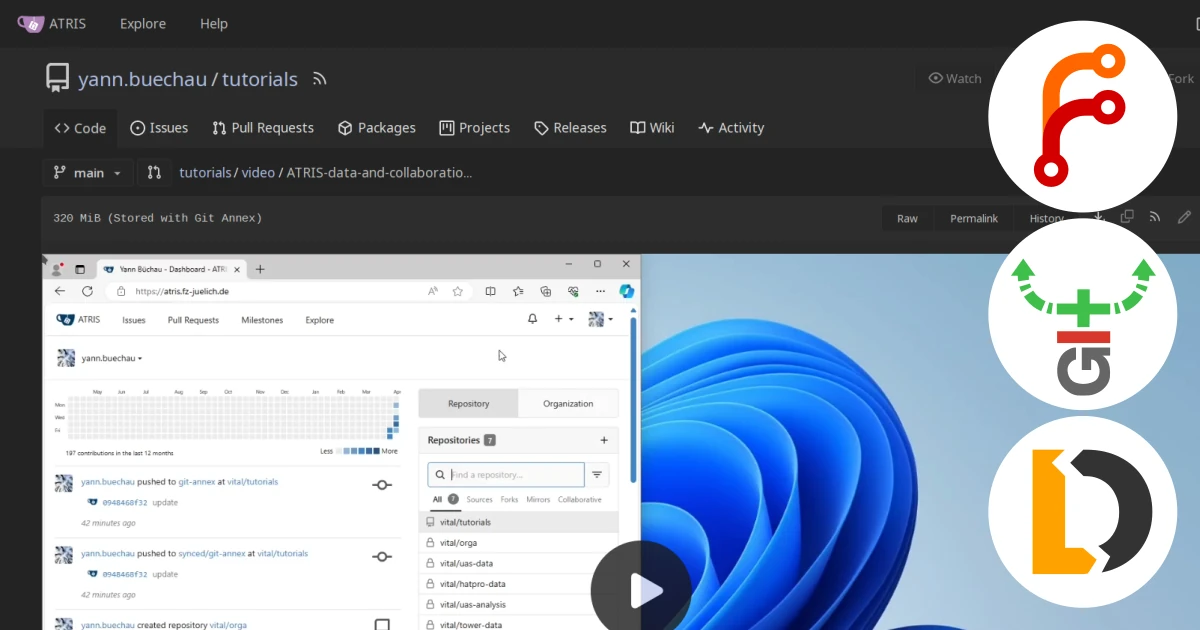

Screenshot of the Forgejo-aneksajo UI (running on the Raspberry Pi) showing the source repository of this blog, and the annex’ed cover image of this post.

Thanks to Adina Wagner, Christian Mönch, Yaroslav Halchenko, and Matthias Riße for providing feedback on a draft of this post.